How gender norms shape women’s engagement and experiences in political institutions and decision-making processes

In conversation with Ján Michalko and Ayesha Khan, Research Fellow and Senior Research Fellow respectively, at ALIGN

ALIGN (short for Advancing Learning and Innovation on Gender Norms) is a digital platform that conducts research that can improve our understanding of discriminatory gender norms. A key thematic focus of their work includes understanding the role of gender norms in shaping political representation, voice and mobilisation.

As part of this area of work, ALIGN recently released a set of seven research reports examining local governance in four countries – Nepal, Nigeria, Peru and Zimbabwe. The reports focus on how gender norms shape women’s engagement with, influence over, and experiences in local governance institutions and decision-making processes.

At #WomenLead, we interviewed Ján Michalko and Ayesha Khan, Research Fellow and Senior Research Fellow respectively at ALIGN to understand the research and ALIGN’s work on women’s political representation better.

In this interview, they help us understand ALIGN’s focus on gender norms better, and explain why they think a norms analysis is essential to understanding why gender gaps in political participation remain some of the most difficult gender gaps to close.

Could you start by sharing a brief overview of the work ALIGN does, particularly your work related to women’s political participation?

Ján Michalko & Ayesha Khan: ALIGN is a flagship digital platform and programme of work of the Gender Equality and Social Inclusion (GESI) team at ODI – a global affairs think tank. ALIGN provides new research, insights from practice, and grants on gender norms and their transformation.

Through its digital platform, as well as its events and activities, ALIGN shares cutting-edge research and diverse resources produced in partnership with practitioners, researchers and thought leaders. Its resources have ranged from ALIGN’s flagship report on gender norms to a comic on feminist activism against period poverty and a toolkit on 10 ways to change gender norms.

Based on our review of existing evidence and research, we have identified various, reinforcing and interconnected pathways to changing harmful and unequal norms. These include the expansion of women’s political participation, investment in education and sexual and reproductive health, and women’s economic empowerment.

These norm changes are motivated by active feminist mobilisations. We research political participation because politics and gender are both about the exercise of power. Understanding how gender intersects with different power structures will, we hope, help to create more equitable power structures.

There is a strong focus on the role of gender norms in the work you do at ALIGN. Could you elaborate on why this particular focus?

Gender norms are the informal and implicit rules and expectations around how men and women should behave in contemporary societies. They are infused into our relationships, institutions and political systems.

Unless they transform these patriarchal gender norms, policies or programmes for gender equality cannot address the root causes of inequalities. While they may be ‘gender aware’ or ‘gender sensitive’, they tend to address the symptoms of inequality, rather than driving long-lasting and sustainable transformation. A norms analysis helps us to understand why gender gaps in political participation remain some of the most difficult gender gaps to close.

Unless they transform these patriarchal gender norms, policies or programmes for gender equality cannot address the root causes of inequalities.

Historically, norms have not been the focus for policy makers or funders who have been interested in women’s political empowerment or gender equality. ALIGN, together with other leading experts on women’s rights, has helped to make gender norms more visible and organisations such as UN agencies or the World Bank are now paying attention to the transformation of harmful norms as a route to equality.

Research and advocacy efforts have highlighted the critical role that political systems – especially the presence of quotas and choice of voting systems – play in determining women’s political participation. In that context, how does a focus on norms help us make sense of the world of politics and women’s representation?

Gender quotas have been crucial in increasing women’s political representation. However, they must be designed and implemented in order to enable women’s meaningful, empowered participation in decision making. Gender norms can help us explain why that does not always happen.

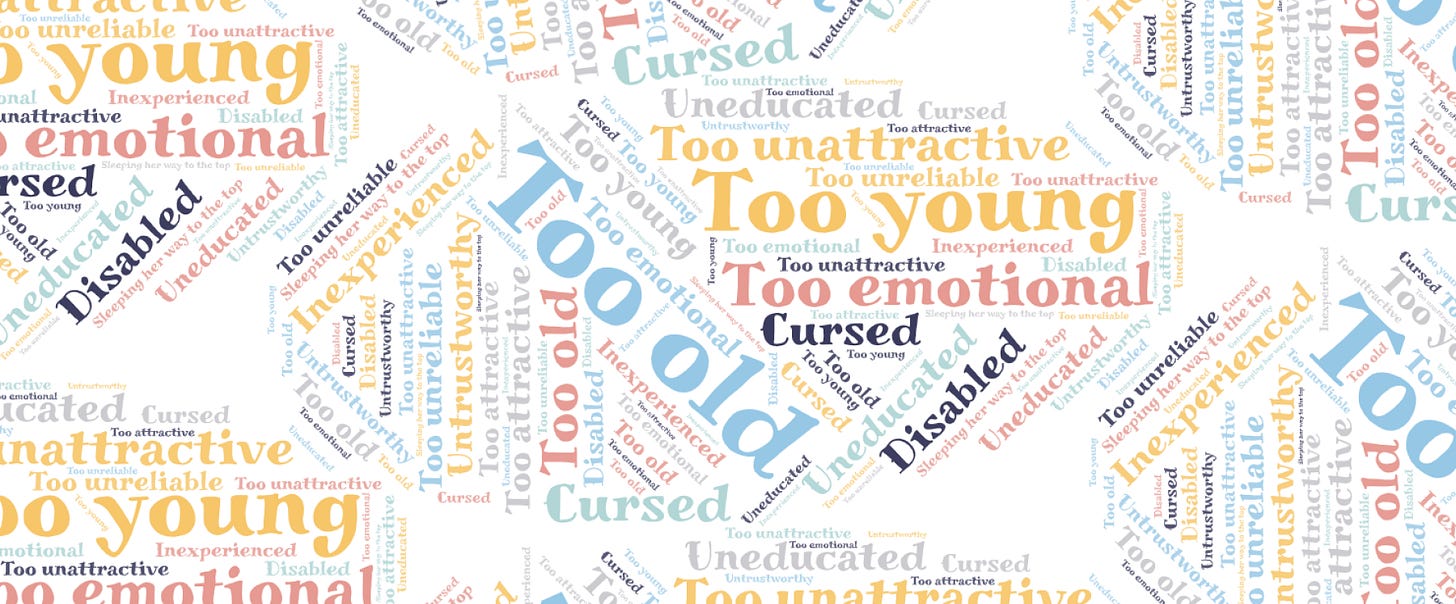

These gender norms are maintained by various strategies, most notably through violence against women in public life, which includes physical threats to their lives, sexual harassment and online attacks on their honour and integrity.

For example, the so-called two-third gender quota system in Kenya – in which no one gender group can hold more than two-thirds of seats – was adopted in 2010 through a constitutional reform; but it has not been implemented. One reason is that many male politicians still believe that women should not be involved in public life. These gender norms are maintained by various strategies, most notably through violence against women in public life, which includes physical threats to their lives, sexual harassment and online attacks on their honour and integrity.

Similarly, many political parties that have adopted quotas continue to undermine women’s ability to exercise power through their mandates. Some parties, often led by men, can circumvent quotas’ impact by nominating women at the bottom of candidate lists so that they are unelectable, or for seats that are hard to win. Parties also operate on informal rules that shape where, when and how politicking is conducted. These can exclude women who, for example, would risk their safety or damage their reputation by meeting men alone.

You have recently released a series of reports that specifically look at gender norms and local governance. What are some of the broad findings? And are there any common patterns or variations across countries?

Many women around the world start their political journeys at the local level where they tend to have close ties to their communities and where their leadership is more visible. So if we can gain a better understanding of their experiences at this level, we can help to ensure that women succeed and thrive at the highest echelons of power.

Although local governance differs from politics at the national level, there are many shared norms and strategies that keep the patriarchal status quo and inequalities alive at both levels. Female councillors, mayors or members of state or provincial parliaments also face high levels of violence – including online – whether from their male colleagues, family members or citizens. At the same time, women who succeed in politics often have strong social networks. These include female colleagues who are role models and mentors, but also husbands, fathers and relatives who support their ambitions.

Many women around the world start their political journeys at the local level where they tend to have close ties to their communities and where their leadership is more visible. So if we can gain a better understanding of their experiences at this level, we can help to ensure that women succeed and thrive at the highest echelons of power.

Our studies also tell us that it is vital to address structural barriers outside of politics, particularly in education and employment. Women often need higher levels of education and qualification than men to be accepted. But even those who are eminently qualified may still be overlooked, and find their credentials disputed. Women also need sources of income to finance their politicking.

Unfortunately, in many countries gender norms lead to women’s lower levels of literacy or exclusion from secondary and higher education. These norms also stop them from taking full advantage of opportunities and employment in the formal economy. Addressing these structural issues would increase women’s ability to participate in formal politics.

How does this new research advance our understanding of the world of politics, not only in the case study countries, but also more broadly?

Local governance and politics have received less attention within the political science discourse on women’s representation than national legislatures and executives. Our research partnerships, therefore, fill important knowledge and evidence gaps both in the countries where our partners work and globally.

For example, very little research had been carried out on the experience of women with disabilities in local politics or in traditional leadership roles. Our partners – Deaf Women Included and TechVillage – conducted unique feminist work by capturing the experiences of women who have been largely neglected by researchers in their studies and theories on politics.

Such exclusion is particularly notable in global political science knowledge production, which has been dominated by scholarship from the so-called global North. ALIGN intentionally supports research in the global majority countries and with institutions that would otherwise be unable to access funding for this important research.

Looking ahead, what are some ongoing and emerging concerns and themes related to women’s political participation that you feel deserve greater attention and research in the near future?

We are working on two key topics that require the urgent attention of scholars and funders as we work towards women’s political equality.

We need to understand how to engage men at the highest levels of power in transformative feminist agendas.

First, we need a better understanding of anti-gender backlash and its close interaction with democratic backsliding. With rising authoritarianism and the reversal of rights of women, LGBTQI+ people and other groups in many countries, there is an urgent need to map how actors who challenge these rights are financed and networked. Equally, we need to assess the policy responses and strategies that are the most effective for progressing global norms around gender equality and the prevention of any further erosion of democratic rights.

Second, we need to understand how to engage men at the highest levels of power in transformative feminist agendas. Some politicians have claimed a feminist identity or have taken on the mantel of gender equality. Yet, the social and political conditions that enable them to do so are under-researched, as is their impact on transforming unequal norms. Understanding if and how we could work with the most powerful men can help to remove barriers to women’s political empowerment and contribute to global gender equity.

This interview is part of our ongoing series that aims to understand the work being done by different initiatives working to close the gender gaps in politics in different parts of the world. The interviews are not meant to be an endorsement of any individual, initiative or political viewpoint.

Read next

A decade of using data to advocate for parity in USA’s politics: Lessons from RepresentWomen’s experience

In August, RepresentWomen, a USA-based organisation working on improving women’s political representation, released the tenth edition of its flagship annual publication, the Gender Parity Index (GPI). The index assesses and tracks women’s representation in elected office at the national, state, and local levels of government in the USA.